Productivity improvements from applying AI to the software development lifecycle have come from relatively predictable layers: better frameworks, more automation in CI/CD, and, more recently, AI autocomplete assistants.

The use of agents introduces something different: they don’t just speed up isolated tasks, they begin to function as a production-support interface where human work is amplified—shifting from writing code toward specifying objectives, planning, and evaluating results.

To clarify what we mean by “agent” in a modern development environment, it is useful to introduce an operational definition based on the concept of specialized agents in tools for task-specific workflows and improved context management.

In this approach, customized sub-agents are specialized assistants invoked for specific types of tasks. They enable more efficient problem solving thanks to specific configurations: custom system prompts, allowed tools, and a separate context window.

Table of contents

Open Table of contents

What are specialized agents?

-

They are preconfigured AI personas to which the system can delegate tasks.

-

They have a specific purpose and area of expertise.

-

They use their own context separated from the main conversation.

-

They can be configured with specific tools.

-

They include a system prompt that guides their behavior.

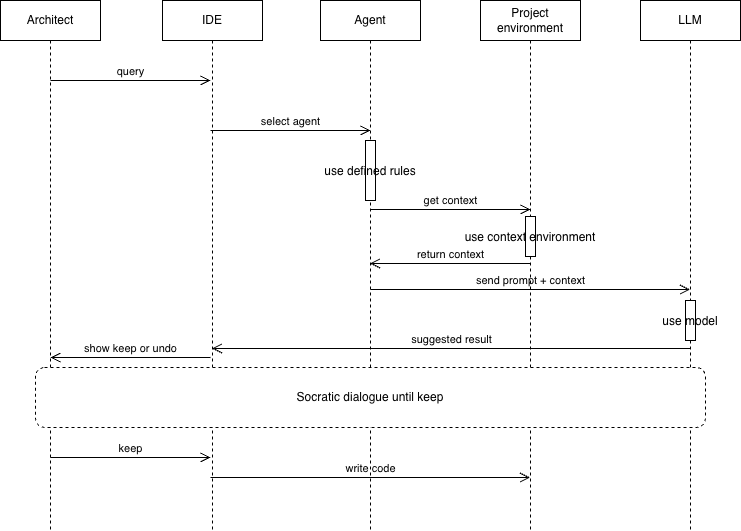

When a task that fits their specialty is detected, it is delegated to that agent, which works independently and returns results.

Key benefits

-

Context preservation: avoids contaminating the main conversation and keeps it focused on high-level goals.

-

Specialization: detailed domain-specific instructions increase the success rate in designated tasks.

-

Reusability: they can be reused across projects and teams.

-

Flexible permissions: tool access can be tailored by sub-agent type.

Adoption of agents in development environments

Real-world adoption of agents in development environments shows significant increases and a tangible shift in work patterns from the perspective of software design and construction.

This shift occurs at two levels:

-

how we build and operate agent-based artificial intelligence

-

how we redesign the software development lifecycle (SDLC) to leverage them without paying hidden costs in quality

In classic autocomplete, the loop is clear: the developer writes and the AI suggests. With agents, the model must be different: the developer assigns an objective, the agent plans and acts, and the person evaluates, corrects, and decides whether to integrate.

And here one of the most distinctive ideas in the use of AI within the SDLC emerges: the best results often don’t come from heavy AI frameworks or conventional input/output model usage, but from simple, specific, composable usage patterns.

Real impact in organizations

There is emerging evidence on the use of agents in large-scale programming environments, visible in the rapid adoption of agents inside an IDE (such as Cursor or Claude Code), with notably fast and cross-cutting uptake: an active user adopts it quickly, with a predominance of experienced software engineers.

In productivity, the indicators are striking when the agent becomes part of the “default” flow, with appreciable increases in generated code and actions within the software lifecycle (such as merges and lines edited) without immediate signs of short-term quality deterioration, and even with reduced bug-fixing dynamics in some scenarios.

Unlike more traditional suggestion tools, agents seem to favor more senior profiles, probably because they know how to delegate better, provide high-value context, and evaluate results more rigorously.

By contrast, the use of AI tools by developers who are only familiar with a narrow specialized form of work and lack a broader software engineering foundation can slow delivery compared to working without AI, due to the cost of verifying and correcting imperfect outputs.

In this sense, we find two scenarios: significant gains when a software development methodology that uses AI for delegation to agents is applied, and micro-costs when AI use is tactical and doesn’t change the method.

If we had to summarize what is truly changing, it would be this: agents shift work from the syntactic plane (writing lines) to the semantic plane (defining intent and evaluating quality). In common usage patterns, most messages to the agent are oriented toward implementation, but a relevant fraction is dedicated to planning, explaining code, or understanding errors. Users who plan first tend to achieve higher acceptance of the outcome. This detail is crucial because it redefines technical excellence: the differentiating value isn’t indicating actions to the agent faster, but formulating the problem better.

A special form of this collaboration between developer and agents is the Socratic Dialogue, a philosophical method of discourse that seeks to foster reflection, self-reflection, and examination of one’s own norms and biases, as well as to promote independent thinking. Just as the philosopher Socrates obtained knowledge by asking specific questions around 450 B.C., a software architect asks the AI questions and evaluates and verifies the answers of the AI system. As in a Socratic dialogue, the query is refined more and more until the architect is satisfied with the results or decides to stop. The collaboration forms considered below are usually based on this type of dialogue.

Proposed patterns and uses

Precise delegation

This is where organizational change becomes visible. A senior engineer can break work into small tasks, ask the agent to implement with tests, and act as integrator and guarantor of coherence with the codebase. Agent effectiveness depends on well-scoped requests. Clear objectives and small tasks turn AI into a reliable execution unit.

Ask for a plan before acting

Before executing, the agent should propose a step-by-step plan with assumptions, risks, and success criteria. This reduces rework and aligns expectations, especially in ambiguous tasks or those with cross-cutting impact. The agent can list technical approaches with pros/cons, trade-offs, and dependencies.

Explicit human review, ideally supported by checklists

All irreversible decisions on architecture, security, or compliance must undergo human review. To avoid quality leaks, the agent’s output should pass through a structured filter. Security, style, performance, and architecture checklists make review consistent and less subjective.

Use in repeatable tasks

Here agents become efficient by automating common, stable work with well-known patterns. Variability is low and verification can be well automated.

The agent can generate standard configurations tailored to a specific, defined tech stack. This saves time and reduces “copy-and-adapt” errors between projects. It helps document operational procedures and diagnostic sequences. Useful for standardizing incident response and reducing dependence on tribal knowledge.

Observability and persistent analysis

Agents can act as continuous diagnostic assistants. With the right context, they help detect patterns, formulate hypotheses, and suggest prioritized actions. They connect signals with probable causes and propose validation steps. This accelerates triage and reduces time to a useful explanation. The agent can recommend small, safe, measurable improvements. It facilitates continuous modernization without slowing the roadmap.

Skills needed for large-scale agent use

- Abstraction: clear mental models of the agent’s capabilities and limits.

- Clarity: precise specifications with explicit constraints.

- Evaluation: critical ability to review code, architecture, security, and complexity.

The success of AI use in the SDLC comes less from the magic of the AI framework used and more from how we design tasks, tools, and evaluations.

AI agents are not just an improvement on autocomplete. They are a proposal for reorganizing work: we shift from “producing code fast” to producing evaluable intent. Evidence in real environments points to substantial gains when the agent is truly integrated into the workflow and when teams develop the ability to delegate with precision.